Martin Luther King (28 August 1963) – 60 years on – Is the Dream Alive?

28 August 2023

Martin Luther King (28 August 1963) – 60 years on – Is the Dream Alive?

28 August 2023

Written by Tim Mitchell, Chair Hartford College, 28 August 2023.

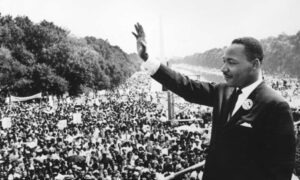

Today marks 60 years since Martin Luther King spoke to the assembled crowd of 250,000 on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. A remarkable, inspired speech, that has echoed around the World ever since.

In the context of education, I wish to focus on these particular words in Dr King’s speech:

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

I’ve always been curious about that turn of phrase – “the content of their character”.

What does it mean?

Martin Luther King Jr. addresses the crowd at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., 28 August, 1963

Our initial response may be to list the qualities that make up good character. Typically, these are virtues, a series of core ethical values to describe good character – honesty, integrity, respect for others, diligence, fortitude, responsibility, fairness, justice, charity, love, compassion. Some lists of virtues run to hundreds of words.

In 1963, Dr King did not suggest that black Americans needed more “content”. Rather, he presumed that his children had it. Dr King assumed that despite their disadvantages, black Americans received “content” for their character from their families, society and their community culture. Content was one advantage they did not lack.

King inferred that the problem was many white Americans judged his people to lack good character. He thought that institutional biases against black Americans made no sense because, if the nation was to rise up and “live out the true meaning of its creed”, all people of good character should be recognised for their virtues and capacity to contribute.

In the early 1960s, it was broadly understood that providing content to inform character was an essential component in the task of teaching youth.

David Brooks, in the current edition of The Atlantic magazine, writes that for “a large part of its history, America was awash in morally formative institutions”. The traditional view was that Americans, like all humanity, are flawed and subject to self-centredness. The founding fathers believed that if Americans were to govern themselves and treat their neighbours decently, they would need to be trained.

Hence when Dr King delivered his “I have a Dream” speech, he presumed a legacy through which the average American, regardless of racial, political or religious affiliation, had acquired a depth of moral formation. It came from myriad institutions: school and community associations, churches, the YMCA, Scouts, professional bodies, worker associations and of course the family itself.

This is not to suggest that everything was halcyon.

In 1916, one newspaper wrote that a Children’s Morality Code was needed because: “In the schools of the United States there is no such thing as character education — a fact that is measurably accountable for the large percentage of young people who grow up into dishonest, lawless or otherwise undesirable citizens”.

But in the early 1960s, Dr King thought that Americans generally were not bereft of opportunities to fill the “content” of their character. Hence, black children should not be presumed to lack those prerequisites for character.

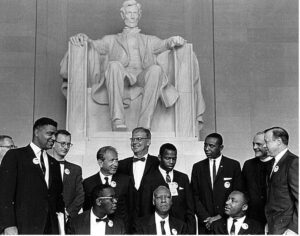

Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders at the Lincoln Memorial on 26 August 1963.

Born in the 1960s, I recall hearing my parents discuss experiences from their youth that seemingly no longer existed for my generation – deportment and elocution classes, grammar, Latin, the Catholic Youth Organisation and penny catechisms.

Then, during and after the 1960s, things radically changed. Moral education retreated as psychological therapy increased. The influence of the aforesaid moral authorities rapidly waned as others filled the void. To our post 60s ears, so much of the old way became prudish and stifling.

Recently, I straw-polled some parents (fellow tail-end boomers and Xers) about use of the word “virtue”. There were two camps. One group said the word harkened up old notions of judgmentalism, over-emphasis on rules, puritanical religiosity, and anti-freedom. The other camp, more contemporaneously, thought it evoked ‘virtue signalling’, a modern day Pharisaism – equally repugnant.

Reflecting then on this tectonic shift since 1963, what would Dr King surmise if he returned today? Like those grainy black and white images at the Lincoln Memorial in 1963, he might see the colour of his dream reduced to grey tones. Many of his people have advanced in previously unimaginable ways, whereas others, in all communities, have declined markedly in social advantage.

Most concerning, what would Dr King have to say about the content of the American people’s character at large?

David Brooks argues that the gradual abandonment of moral authority has left too many seeking in places where they will not find resolution:

“We inhabit a society in which people are no longer trained in how to treat others with kindness and consideration…

Expecting people to build a satisfying moral and spiritual life on their own by looking within themselves is asking too much. A culture that leaves people morally naked and alone leaves them without the skills to be decent to one another.”

Of course, this is not to portray our culture as on a highway to hell. One must be wary of imbalanced pessimism – as if there is no hope. On the contrary, Hope is one of the three theological virtues that we must strive to seek. It springs from faith and is a key to charity, optimism and a sense of joy in daily existence.

At Hartford College, we are immensely optimistic about the renewed global interest in character education. This movement manifests in many ways but essentially it seeks to train the whole person, both in learning to love learning but also in the formation of each student’s character.

Working hard to ensure that our children receive “content” for their character is challenging. We must work closely with parents and balance formation with the achievement of academic excellence.

Schools have to operate within a certain economy. The economy of time, teacher resources, student capabilities and regulatory requirements. But working hard on an integrated Liberal Arts curriculum means we can enmesh the learning that fuels a desire for good character with the standards of knowledge that we expect from a well-run school.

There is a certain urgency as ongoing reports of declining educational standards and increasing social malaise attest. It’s been reported this year that the percentage of year 9 boys in Australia who didn’t meet the minimum standard in reading nationally is now one in eight, up from one in twelve in 2018.

In a modern iteration of Dr King’s dream, we dream of a school that fills the content of the character of our students. Our Christian faith tradition complements and enhances a thirst to discover the secrets of God’s incredible universe, both within ourselves and without.

60 years on, were Dr King to alter his dream for 2023, he might hope that all children would receive content for their character. That in a spirit of freedom and love of knowledge, all children might have the opportunities they deserve for personal fulfilment. We thank Dr King for his dreams … and we dare to dream on.

Daceyville

NSW 2032

(02) 9184 8840

Hartford Policies